A Brush With Death Read Online Free

A young Ernest Hemingway, badly injured by an exploding shell on a World State of war I battlefield, wrote in a letter home that "dying is a very simple thing. I've looked at death, and really I know. If I should accept died information technology would take been very easy for me. Quite the easiest matter I ever did."

Years later Hemingway adapted his own feel—that of the soul leaving the torso, taking flight so returning—for his famous curt story "The Snows of Kilimanjaro," about an African safari gone disastrously wrong. The protagonist, stricken by gangrene, knows he is dying. All of a sudden, his pain vanishes, and Compie, a bush pilot, arrives to rescue him. The ii accept off and wing together through a storm with rain and then thick "information technology seemed like flying through a waterfall" until the plane emerges into the light: before them, "unbelievably white in the sun, was the square top of Kilimanjaro. And so he knew that there was where he was going." The description embraces elements of a classic near-death experience: the darkness, the cessation of pain, the emerging into the light and and so a feeling of peacefulness.

Peace Beyond Agreement

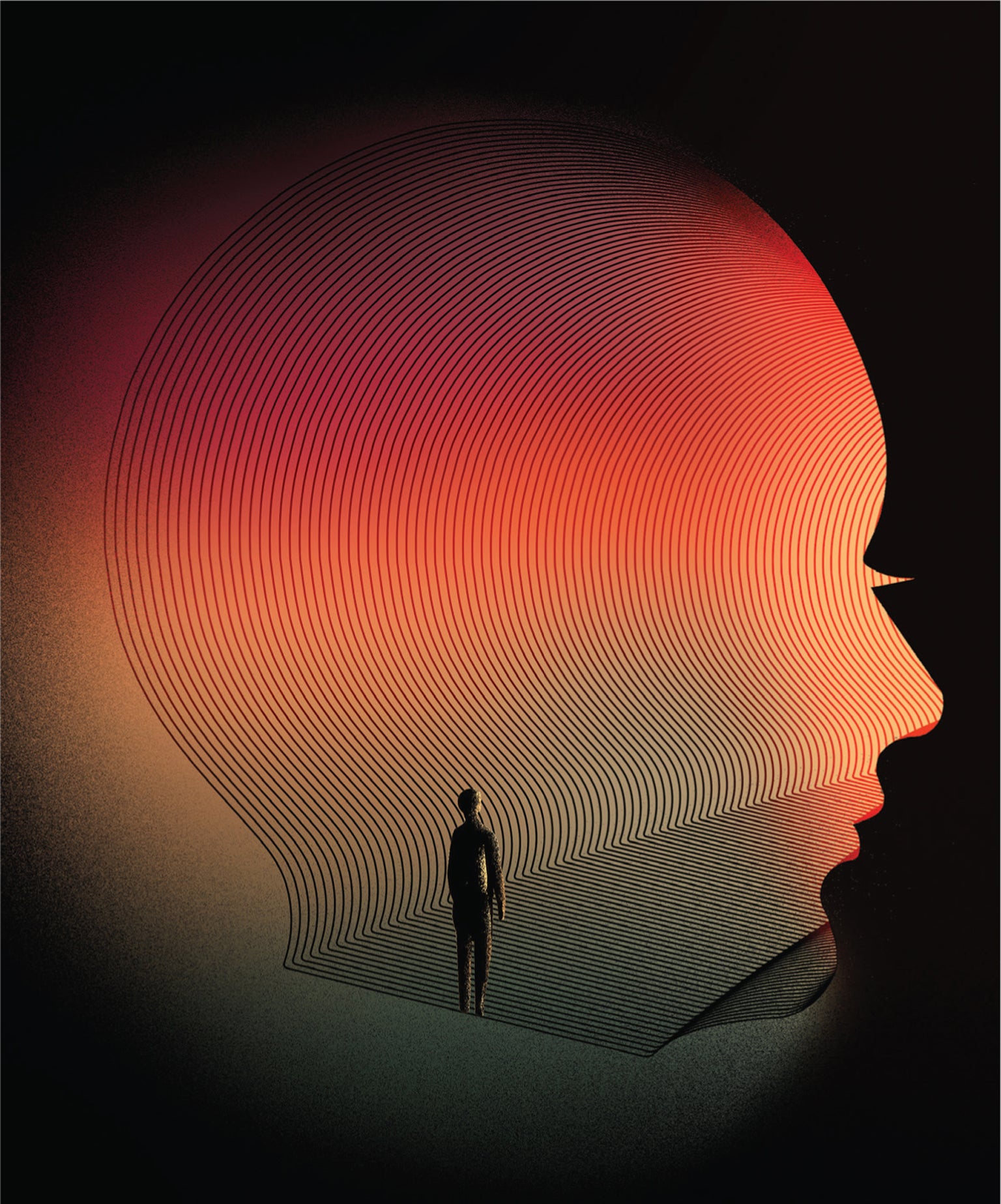

Almost-decease experiences, or NDEs, are triggered during singular life-threatening episodes when the body is injured past edgeless trauma, a heart assault, asphyxia, daze, and so on. About one in 10 patients with cardiac abort in a hospital setting undergoes such an episode. Thousands of survivors of these harrowing impact-and-go situations tell of leaving their damaged bodies behind and encountering a realm beyond everyday existence, unconstrained by the usual boundaries of space and fourth dimension. These powerful, mystical experiences tin atomic number 82 to permanent transformation of their lives.

NDEs are not fancy flights of the imagination. They share broad commonalities—becoming hurting-gratis, seeing a bright lite at the end of a tunnel and other visual phenomena, detaching from one's body and floating above information technology, or fifty-fifty flying off into space (out-of-body experiences). They might include meeting loved ones, living or dead, or spiritual beings such equally angels; a Proustian recollection or fifty-fifty review of lifetime memories, both good and bad ("my life flashed in forepart of my eyes"); or a distorted sense of time and space. In that location are some underlying physiological explanations for these perceptions, such as progressively narrowing tunnel vision. Reduced blood flow to the visual periphery of the retina ways vision loss occurs there first.

NDEs can be either positive or negative experiences. The former receive all the press and relate to the feeling of an overwhelming presence, something numinous, divine. A jarring disconnect separates the massive trauma to the trunk and the peacefulness and feeling of oneness with the universe. Nonetheless not all NDEs are blissful—some tin can be frightening, marked by intense terror, ache, loneliness and despair.

It is likely that the publicity around NDEs has built up expectations about what people should feel after such episodes. Information technology seems possible, in fact, that distressing NDEs are significantly underreported considering of shame, social stigma and pressure to conform to the prototype of the "blissful" NDE.

Whatever close brush with death reminds us of the precariousness and fragility of life and tin can strip away the layers of psychological suppression that shield us from uncomfortable thoughts of existential oblivion. For most, these events fade in intensity with time, and normality eventually reasserts itself (although they may leave post-traumatic stress disorder in their wake). Only NDEs are recalled with unusual intensity and lucidity over decades.

A 2017 study past two researchers at the Academy of Virginia raised the question of whether the paradox of enhanced cognition occurring aslope compromised brain part during an NDE could be written off equally a flight of imagination. The researchers administered a questionnaire to 122 people who reported NDEs. They asked them to compare memories of their experiences with those of both real and imagined events from about the aforementioned fourth dimension. The results suggest that the NDEs were recalled with greater vividness and particular than either real or imagined situations were. In short, the NDEs were remembered as beingness "realer than real."

NDEs came to the attending of the full general public in the last quarter of the 20th century from the work of physicians and psychologists—in particular Raymond Moody, who coined the term "near-death experience" in his 1975 best seller, Life subsequently Life, and Bruce 1000. Greyson, one of the two researchers on the written report mentioned earlier, who also published The Handbook of Near-Decease Experiences in 2009. Noticing patterns in what people would share about their nearly-death stories, these researchers turned a phenomenon once derided as confabulation or dismissed as feverish hallucination (deathbed visions of yore) into a field of empirical study.

I accept the reality of these intensely felt experiences. They are every bit authentic as any other subjective feeling or perception. As a scientist, however, I operate under the hypothesis that all our thoughts, memories, percepts and experiences are an ineluctable event of the natural causal powers of our encephalon rather than of whatever supernatural ones. That premise has served science and its handmaiden, technology, extremely well over the past few centuries. Unless at that place is extraordinary, compelling, objective evidence to the contrary, I see no reason to abandon this supposition.

The claiming, so, is to explain NDEs within a natural framework. Every bit a longtime student of the mind-body trouble, I care near NDEs because they plant a rare diversity of human consciousness and because of the remarkable fact that an consequence lasting well nether an hour in objective time leaves a permanent transformation in its wake, a Pauline conversion on the road to Damascus—no more than fear of death, a detachment from fabric possessions and an orientation toward the greater good. Or, as in the case of Hemingway, an obsession with run a risk and death.

Similar mystical experiences are commonly reported when ingesting psychoactive substances from a course of hallucinogens linked to the neurotransmitter serotonin, including psilocybin (the agile ingredient in magic mushrooms), LSD, DMT (aka the Spirit Molecule), and five-MeO-DMT (aka the God Molecule), consumed as part of religious, spiritual or recreational practices.

The Undiscovered Land

Information technology must be remembered that NDEs have been with usa at all times in all cultures and in all people, young and sometime, devout and skeptical (retrieve, for instance, of the so-called Tibetan Volume of the Expressionless, which describes the mind before and afterward decease). To those raised in religious traditions, Christian or otherwise, the most obvious explanation is that they were granted a vision of heaven or hell, of what awaits them in the hereafter. Interestingly, NDEs are no more probable to occur in devout believers than in secular or nonpracticing subjects.

Personal narratives drawn from the historical record furnish intensely vivid accounts of NDEs that can be as instructive as any dry, clinical case report, if not more so. In 1791, for instance, British admiral Sir Francis Beaufort (later on whom the Beaufort current of air scale is named) almost drowned, an consequence he recalled in this fashion:

A calm feeling of the most perfect tranquility succeeded the most tumultuous sensation…. Nor was I in whatsoever bodily pain. On the opposite, my sensations were now of rather a pleasurable cast .... Though the senses were thus deadened, not so the mind; its activeness seemed to be invigorated in a ratio which defies all description; for thought rose subsequently thought with a rapidity of succession that is not merely indescribable, but probably inconceivable, by anyone who has been himself in a similar state of affairs. The grade of these thoughts I tin can even now in a great measure out retrace: the event that had just taken place .... Thus, traveling backwards, every incident of my past life seemed to me to glance across my recollection in retrograde procession ... the whole period of my existence seemed to exist placed earlier me in a kind of panoramic view.

Another instance was recorded in 1900, when Scottish surgeon Sir Alexander Ogston (discoverer of Staphylococcus) succumbed to a tour of typhoid fever. He described what happened this way:

I lay, equally information technology seemed, in a constant stupor which excluded the existence of any hopes or fears. Mind and body seemed to exist dual, and to some extent split. I was conscious of the torso as an inert tumbled mass near a door; information technology belonged to me, but it was not I. I was conscious that my mental self used regularly to leave the torso .... I was then drawn chop-chop back to it, joined information technology with disgust, and information technology became I, and was fed, spoken to, and cared for .... And though I knew that death was hovering about, having no thought of religion nor dread of the stop, and roamed on beneath the murky skies apathetic and contented until something again disturbed the body where information technology lay, when I was drawn back to it afresh.

More than recently, British writer Susan Blackmore received a report from a woman from Cyprus who had an emergency gastrectomy in 1991:

On the fourth day following that functioning I went into shock and became unconscious for several hours .... Although thought to be unconscious, I remembered, for years later, the unabridged, detailed conversation that passed betwixt the surgeon and anaesthetist present .... I was lying above my own body, totally complimentary of pain, and looking down at my own self with compassion for the agony I could see on the face; I was floating peacefully. Then ... I was going elsewhere, floating towards a night, but not frightening, drapery-like surface area ... Then I felt full peace. Suddenly it all changed—I was slammed back into my body over again, very much enlightened of the desperation again.

The underlying neurological sequence of events in a near-expiry experience is difficult to decide with whatsoever precision because of the dizzying diversity of ways in which the brain tin can exist damaged. Furthermore, NDEs do non strike when the individual is lying inside a magnetic scanner or has his or her scalp covered past a net of electrodes.

It is possible, though, to proceeds some idea of what happens by examining a cardiac arrest, in which the heart stops beating (the patient is "coding," in hospital jargon). The patient has non died, because the heart tin can exist jump-started via cardiopulmo-nary resuscitation.

Modern death requires irreversible loss of brain function. When the brain is starved of claret flow (ischemia) and oxygen (anoxia), the patient faints in a fraction of a minute and his or her electroencephalogram, or EEG, becomes isoelectric—in other words, flat. This implies that large-scale, spatially distributed electrical activeness within the cortex, the outermost layer of the brain, has broken downwardly. Like a town that loses power 1 neighborhood at a time, local regions of the brain go offline one after another. The heed, whose substrate is whichever neurons remain capable of generating electrical activity, does what it ever does: information technology tells a story shaped by the person'southward feel, memory and cultural expectations.

Given these power outages, this experience may produce the rather strange and idiosyncratic stories that brand up the corpus of NDE reports. To the person undergoing information technology, the NDE is as real equally anything the mind produces during normal waking. When the entire brain has shut down because of complete ability loss, the listen is extinguished, along with consciousness. If and when oxygen and blood flow are restored, the brain boots up, and the narrative flow of feel resumes.

Scientists have videotaped, analyzed and dissected the loss and subsequent recovery of consciousness in highly trained individuals—U.S. test pilots and NASA astronauts in centrifuges during the cold state of war (recollect the scene in the 2018 movie First Homo of a stoic Neil Armstrong, played by Ryan Gosling, being spun in a multiaxis trainer until he passes out). At around five times the force of gravity, the cardiovascular system stops delivering claret to the brain, and the pilot faints. Virtually x to xx seconds after these large g-forces finish, consciousness returns, accompanied by a comparable interval of confusion and disorientation (subjects in these tests are plainly very fit and pride themselves on their self-control).

The range of phenomena these men recount may amount to "NDE low-cal"—tunnel vision and brilliant lights; a feeling of awakening from sleep, including fractional or complete paralysis; a sense of peaceful floating; out-of-trunk experiences; sensations of pleasure and fifty-fifty euphoria; and curt simply intense dreams, often involving conversations with family members, that remain brilliant to them many years afterward. These intensely felt experiences, triggered by a specific physical insult, typically practice not have any religious graphic symbol (perhaps because participants knew ahead of time that they would be stressed until they fainted).

By their very nature, NDEs are not readily amenable to well-controlled laboratory experimentation, although this might change. For case, it may be possible to study aspects of them in the humble lab mouse—perhaps it, too, can experience a review of lifetime memories or euphoria before expiry.

The Fading of the Low-cal

Many neurologists have noted similarities betwixt NDEs and the effects of a class of epileptic events known as complex partial seizures. These fits partially impair consciousness and often are localized to specific brain regions in one hemisphere. They can be preceded by an aura, which is a specific feel unique to an private patient that is predictive of an incipient attack. The seizure may be accompanied by changes in the perceived sizes of objects; unusual tastes, smells or bodily feelings; déjà vu; depersonalization; or ecstatic feelings. Episodes featuring the last items on this list are also clinically known as Dostoyevsky'due south seizures, afterwards the tardily 19th-century Russian author Fyodor Dostoyevsky, who suffered from severe temporal lobe epilepsy. Prince Myshkin, the protagonist of his novel The Idiot, remembers:

During his epileptic fits, or rather immediately preceding them, he had always experienced a moment or ii when his whole heart, and mind, and torso seemed to wake up to vigor and light; when he became filled with joy and hope, and all his anxieties seemed to be swept away forever; these moments were but presentiments, every bit it were, of the one terminal second (it was never more than a second) in which the fit came upon him. That second, of class, was inexpressible. When his attack was over, and the prince reflected on his symptoms, he used to say to himself: ... "What matter though it be but illness, an abnormal tension of the encephalon, if when I think and clarify the moment, it seems to have been one of harmony and beauty in the highest degree—an instant of deepest sensation, overflowing with unbounded joy and rapture, ecstatic devotion, and completest life? ... I would give my whole life for this one instant.

More than 150 years later neurosurgeons are able to induce such ecstatic feelings by electrically stimulating office of the cortex chosen the insula in epileptic patients who have electrodes implanted in their brain. This procedure can assistance locate the origin of the seizures for possible surgical removal. Patients report elation, enhanced well-being, and heightened cocky-awareness or perception of the external globe. Exciting the grey matter elsewhere can trigger out-of-body experiences or visual hallucinations. This brute link between abnormal activity patterns—whether induced by the spontaneous disease process or controlled past a surgeon'southward electrode—and subjective experience provides support for a biological, not spiritual, origin. The same is likely to exist truthful for NDEs.

Why the mind should experience the struggle to sustain its operations in the face of loss of blood flow and oxygen as positive and blissful rather than as panic-inducing remains mysterious. It is intriguing, though, that the outer limit of the spectrum of human experience encompasses other occasions in which reduced oxygen causes pleasurable feelings of jauntiness, lite-headedness and heightened arousal—deepwater diving, high-altitude climbing, flying, the choking or fainting game, and sexual asphyxiation.

Perchance such ecstatic experiences are mutual to many forms of decease as long as the heed remains lucid and is non dulled past opiates or other drugs given to convalesce pain. The mind, chained to a dying trunk, visits its own individual version of heaven or hell before inbound Hamlet'due south "undiscovered country from whose bourn no traveler returns."

This article was originally published with the title "Tales of the Dying Brain" in Scientific American 322, 6, 70-75 (June 2020)

doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0620-seventy

Source: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/what-near-death-experiences-reveal-about-the-brain/

0 Response to "A Brush With Death Read Online Free"

Post a Comment